Make sure you have the knowledge and training you need before any complaints surface.

By: Dori Meinert

The general manager of a Massachusetts car dealership testified at trial that he “honestly didn’t believe” a finance manager when she told him that her supervisor often commented on her anatomy, tried to throw coins down her blouse and suggested they sleep together so he could see her breasts.

The finance manager, who was fired after making complaints, ultimately was awarded $200,000 in punitive damages because her employer failed to properly investigate her allegations. That’s on top of $40,000 in compensatory damages for emotional distress.

In ruling that punitive damages were warranted, the state’s high court issued a scathing review of the company’s handling of the woman’s grievances. In fact, it reads like a primer on what not to do in sexual harassment inquiries.

“The investigation was marred from the beginning” because of the general manager’s bias against the accuser, according to the court. The general manager and the HR manager at Lexus of Watertown Inc. claimed to have conducted separate investigations but couldn’t produce any notes. And the court found it particularly concerning that they couldn’t find anything to support the woman’s allegations, even though many of the incidents she reported were supported by other employees at trial.

The case is just one example of how a poorly conducted investigation can harm an organization’s bottom line as well as its long-term reputation.

In the recent flood of sexual harassment allegations involving high-profile individuals in various industries, HR professionals have been criticized for being unwilling or unable to investigate such complaints. They’ve been accused of protecting their organizations, or at least the powerful individuals at their helms, at the expense of the harassed workers.

“Whether that’s true or not, there is clearly often the perception that HR is not working for employees,” which needs to be addressed, says Elaine Herskowitz, a former staff attorney with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) who drafted several key EEOC policies on sexual harassment three decades ago and now is a consultant.

One way HR professionals can shift that view is to make sure they get the knowledge and training they need to conduct prompt, objective and thorough investigations—before a complaint comes in, Herskowitz and others say.

In fact, some HR leaders are asking experts to guide them through mock investigations to give them more practice, while others are requesting workplace climate assessments in an effort to uncover problems earlier. No one wants to wake up one morning and find their company in the news.

Mounting Concern

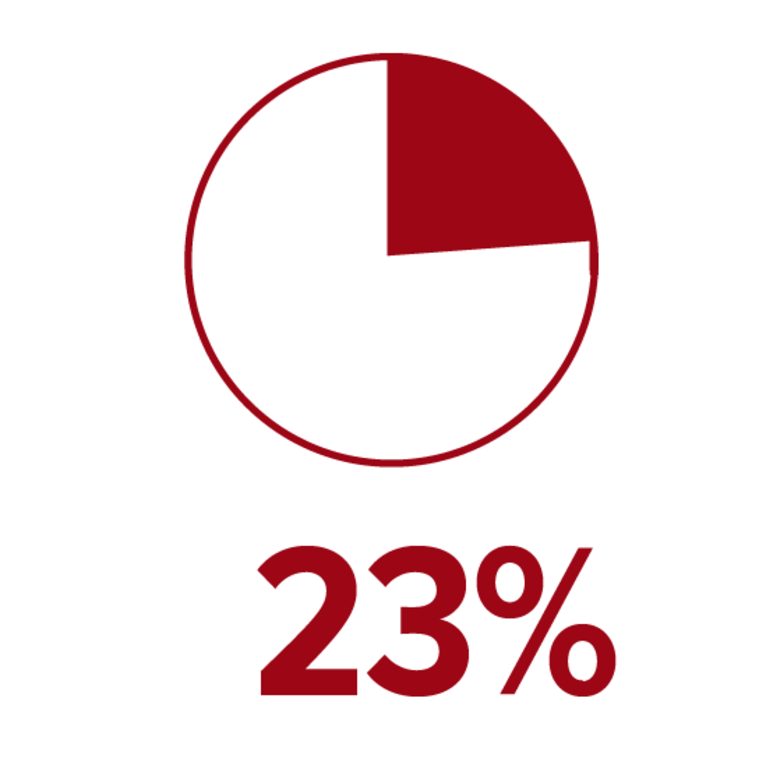

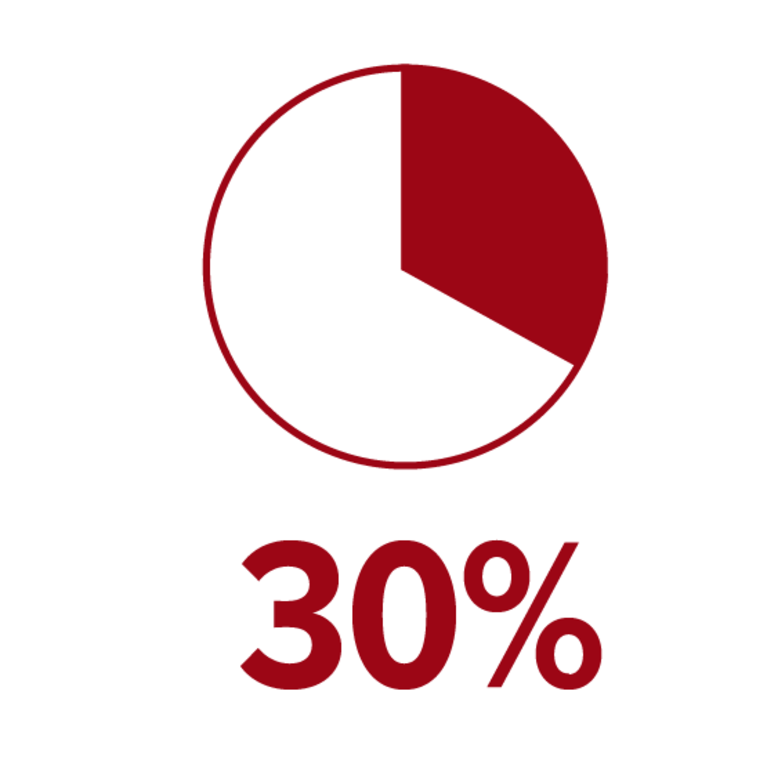

Almost two-thirds of Americans, or 64 percent, say sexual harassment in the workplace is a serious problem, up from 47 percent in 2011, according to a recentWashington Post-ABC News poll. Thirty percent of women surveyed have experienced unwanted sexual advances from male co-workers, and 23 percent said they were harassed by men who had influence over their jobs. Of those who reported being subjected to harassment at work, one-third said they were sexually abused. Only 42 percent of the women reported the inappropriate behavior to a supervisor, and 95 percent said the men went unpunished.

While some suggest HR must choose sides—the employer or the employee—many practitioners don’t believe the two are mutually exclusive.

Maggie Snape, HR director for Fuss & O’Neill, an engineering company in Manchester, Conn., says she believes HR’s role is to protect the organization. “But that being said, especially in sexual harassment situations … the best way that HR can protect the company is to make sure they find out what’s going on and remove any people from the workforce who are doing this. So, protecting the employees is really protecting the company.”

The Challenge

While workplace investigations in general are considered one of the toughest parts of an HR professional’s duties, investigating sexual harassment complaints can be particularly challenging.

“It’s an embarrassing subject for folks, which is why we often don’t hear about it for decades,” says Judy Clark, owner of HR Answers Inc., in Tigard, Ore. “In most situations, it’s not about sex, it’s about an abuse of power.”

So, it’s very difficult for someone new to a job or in a low-level position to report harassment, Clark says. “It’s not just that they’re afraid of coming to HR. They’re afraid of the consequences. ‘What happens if I lose my job? What happens if I’m identified as a troublemaker? What happens if I lose my job and they give me a bad reference?’ ”

Frequently, the employee who is being harassed just wants the offensive behavior to stop, she says. That’s why it’s important to be sensitive to the individual’s turmoil, explaining that, “We don’t want you to be subjected to this. We have to look into this.” Then determine whether it’s necessary to take steps to protect the individual’s physical safety and to block any retaliation.

All sexual harassment allegations should be investigated, although some inquiries will be more extensive than others. If you write anybody off, you could later be accused of not taking their complaints seriously, Clark says.

Likewise, she notes, a superficial or sloppy investigation will send the message to employees “that the organization doesn’t care, that the organization thinks I’m lying, that they’re protecting a person of power.” And an employee who might have been upset and sad before could turn angry. “Mad means money in court,” Clark says.

|

What Is Sexual Harassment? Sexual harassment includes unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). It also can include offensive remarks about a person’s gender. Both the victim and the harasser can be either a woman or a man, and the victim and harasser can be the same sex. The harasser can be the victim’s supervisor, a manager in another area, a co-worker or someone who is not an employee, such as a client or customer. Sexual harassment is considered illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile work environment or adversely affects the victim’s job, such as being fired or demoted. Would a reasonable person find the conduct offensive? That’s the standard used by the courts and the EEOC. |

Make a Plan

One of the biggest mistakes HR makes is failing to create an investigative plan before diving into interviews, says Britt-Marie Cole-Johnson, an employment lawyer in Hartford, Conn., who is also on the board of the Association of Workplace Investigators.

The first step is to determine the scope of the investigation, she says. What is the main question the investigator wants to answer?

HR professionals often come to her wondering how they got off track. They start an inquiry but then it grows until they feel like they’re conducting multiple investigations. “It’s classic scope creep. You have to make a decision. Is this related to the original investigation? Do I need to launch a new investigation? When do I have enough?”

Having a plan will help guide the investigator through the various steps, she says.

Other questions to address in the plan include:

- Who will investigate?

- What evidence needs to be collected?

- Who will be interviewed?

To protect the credibility of the process, you may want to bring in an outside investigator. That’s a good idea, for example, when the person accused is a high-level executive or if those on the HR team lack the experience and training to conduct such an inquiry themselves.

“In my current role, I work closely with the C-suite every day,” Snape says. “If I was conducting an investigation about one of them, other people in the company might have a hard time believing in my objectivity because these are people I work with day in and day out.”Choosing an objective third party not only provides a stronger defense for the employer if a case ever goes to court, it can also make it easier for business leaders to make the right decision, even if it means terminating someone who is a strong financial asset.“If the person who is accused of harassment has any control over HR, then it [HR] is not a neutral, objective investigator,” says Herskowitz, principal with EEO Training & Consulting, which has offices in New York and Maryland.

Stay Neutral

From the beginning, the investigator should maintain a neutral, objective demeanor.

“It’s important not to label the parties as ‘victim’ and ‘harasser,’ as that creates the appearance—and a very real possibility—of a predetermined resolution,” Snape says. “If you go into this thinking this person is a victim, there’s a very good possibility that your investigatory questions are going to be swayed and not be as objective as needed to make a decision.”

For example, Bonnie Turner, SHRM-SCP, director of HR at Elkhart Plastics Inc. in South Bend, Ind., recalls one case involving a female employee who alleged a male co-worker was sexually harassing her. Turner later learned that the two were having a consensual affair, and the woman made the complaint to hide that fact from her husband.

Some basic steps for every investigation include the following:

Prepare interview questions in advance. Collect needed details from the person making the allegation—the who, what, when and where. You might also ask “Were there witnesses? Did others know you were upset by this? Did you talk to family members or friends?”

Try to ask open-ended questions to ensure that you have a full picture of events.

Resist the urge to fill silent moments. Staying quiet can be helpful when you’re trying to get someone to open up, Clark advises. She suggests saying, “I have the feeling that you want to say more about that.” Then, wait.

*said they were harassed by men who had influence over their jobs.

Gather evidence that might support or negate the complaint. This might include voice mails, text messages, e-mails, photos, timecards, business expense records and social media posts. For example, electronic messages might show that a male supervisor made inappropriate sexual comments to a female subordinate. On the flip side, if workers need a key card to enter the worksite, building access records might show that the person accused likely wasn’t in the building at the time of the alleged incident, Cole-Johnson suggests.

Check past performance evaluations and prior complaints. Consider whether the person making the allegation might be seeking retribution for a poor evaluation. “You have to leave your mind open to all of this. Unfortunately, this sometimes happens,” although less frequently than some suggest, Clark says.

Also evaluate any past complaints against the person being accused. Contact former employees, particularly the individual who previously held the accuser’s job or anyone in the same department who left suddenly without explanation, to find out if they also had problems with the accused employee, Clark recommends.

Even if there are no prior complaints, you might detect a pattern of questionable behavior. Sometimes the problem escalates over time. That was the case with a female employee in a medical office who was asked by a doctor to stay late frequently to review the day’s cases over drinks. The situation became more personal and sexually charged than she wanted it to be—and she didn’t know how to get out of it, Clark says.

Document every step. Take careful notes throughout the interviews. Record who wasn’t available and why. Some HR professionals even ask interviewees to sign off on the written summaries of their statements. Be aware that any written evidence might well end up being scrutinized in court.

Encourage confidentiality. Ask those you’ve interviewed to keep the conversations confidential. But don’t mandate it. The National Labor Relations Board has said employers can’t prohibit employees from discussing working conditions, including workplace investigations, says Susan White, SHRM-SCP, chief executive officer of Susan Tinder White Consulting LLC in Indianapolis. Instead, encourage them to help you with the investigation by not discussing it with others, she advises.

That goes for the HR team as well. A sexual harassment investigation “can’t be treated as juicy gossip, drama or a soap opera,” Snape says. “It can have such a long-lasting effect on the company and people’s careers.”

Make a Decision

Ultimately, you’ll need to decide whether a company policy was violated or inappropriate conduct occurred and recommend a course of action to the decision-maker.

“Don’t just regurgitate what the witnesses told you. That’s not the role of an investigator,” advises Cole-Johnson, the lawyer and trained investigator. Weigh the evidence. Can you corroborate details of each person’s version? Does either person have a reason to lie? The EEOC offers guidelines for determining credibility.

Cole-Johnson has seen some investigative reports that dismiss someone’s account as not credible because of their “demeanor.” When asked to explain, the investigator has said the individual didn’t look them in the eye during the interview. The average HR person is not trained to assess that, she notes. “It’s not the most culturally competent thing to be doing either,” she says, since looking someone in the eye is disrespectful in some cultures.

While EEOC guidelines recommend that investigators examine witnesses’ demeanors, researchers have found that it’s actually a poor way to spot deception, says Michael Wade Johnson, CEO of Clear Law Institute and a former U.S. Department of Justice attorney. Investigators primarily look for nervousness. However, a person may be nervous or fidgety even when telling the truth.

Inexperienced investigators may find it difficult to reach a decision because they don’t understand that they’re not running a criminal case where the standard for evidence is “beyond a reasonable doubt,” Cole-Johnson says. Here, the standard is “preponderance of the evidence.” In other words, is it more likely than not that the incident occurred?

In one investigation, Herskowitz came down on the side of a female contract employee who shared with a co-worker that she had been sexually assaulted by a warehouse supervisor. “What I found compelling is that she didn’t even want this [investigation] to be happening. She felt very vulnerable because of her job,” she says. “He had every reason to lie. She had no reason to lie.”

Write a Report

While the EEOC recommends a «prompt” investigation when harassment claims are made, that doesn’t mean you should speed through it.

“In my mind, it’s better to do it right than to just get through it and have some sort of public punishment. That should never be the goal,” Cole-Johnson says. “The goal is to produce an appropriate fact-finding document or report … Sometimes that can be done quickly, especially if there are only a couple of witnesses, and sometimes that’s not feasible,” she says.

If the allegations are supported, the employer should take immediate and appropriate corrective action, which could range from a written reprimand to termination of employment depending on the severity and frequency of the misconduct, experts say. Make sure high-level employees are given the same treatment as low-level employees for similar conduct.

The EEOC recommends that the written report document the investigation process, findings, recommendations and any disciplinary action imposed, as well as any corrective and preventive action.

After you’ve submitted the written report to the decision-maker and determined the appropriate disciplinary action (if any), follow up with both parties. Tell the person who filed the complaint that appropriate action was taken, even if you can’t share the details for privacy reasons.

Check back with that employee regularly to ensure that no further harassment has occurred and that there has been no retaliation, which could trigger additional liability.

That follow-up shows the person who made the complaint that HR took it seriously, White says. In many highly publicized recent cases, the alleged sexual harassment and abuse reportedly had been an open secret for years. After one person came forward, the floodgates opened.

“You don’t want to be the HR professional in your company who has 30 people come forward saying this has been going on for years,” Snape says.

|

Measuring Credibility When there are conflicting versions of events in harassment cases, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission suggests using the following factors to assess the credibility of all involved individuals: Plausibility. Is the individual’s version of the facts believable? Are there inconsistencies? Demeanor. Does the individual seem to be telling the truth? This can be tricky. Contrary to popular belief, a liar might look you in the eye, while someone telling the truth could avert their gaze. Instead of being fidgety, liars are more likely to be rigid, says Michael Wade Johnson, CEO of Clear Law Institute and a former U.S. Department of Justice attorney. Motive. Does the individual have a reason to lie? Corroboration. Are there documents or other witnesses that support the individual’s version of events? Past record. Do any of the individuals have a prior history of inappropriate conduct or false statements? |

Dori Meinert is senior writer/editor for HR Magazine. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0218/pages/how-to-investigate-sexual-harassment-allegations.aspx